|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 10 mins

Proceedings from the 1st Annual Symposium on the Grenadian Revolution of 1979 – 1983, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, October 19, 2017

Harlem (“What happens to a dream deferred?”)

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

Like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

Like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

– Langston Hughes (1951)

Incidentally this poem was penned in 1951, a year of massive labor upheavals in Grenada led by Eric Matthew Gairy, founder of the Grenada United Labour Party. That year culminated in a general strike for better working conditions for agricultural workers. These events were dubbed ‘red sky’ because of the many buildings that were engulfed in flames. British authorities were forced to bring in military reinforcements to control the situation. But among the victories gained was that on October 10, 1951 Grenada held its first general elections on the basis of universal adult suffrage. Keen followers of our history will see similar patterns of this ebb and flow of struggles (gains and losses), virtually all major turning points ending in foreign interventions/invasions. Major disappointment and successes co-existing; a peaceful, communal lifestyle of the people side by side with state violence. Within the last close to 70 years – from 1951 to the present – Grenada experienced four different manifestation of state violence – the British colonial state, Gairy’s authoritarian rule, the heavy manners at the end of the Grenada Revolution, and the persistent destabilization and ultimate invasion by the US state.

We are faced with the fact that Grenada has been and remains today one of the countries with the lowest murder rates in the Caribbean throughout the last 70 or so years. Yet the country has experienced one of the highest levels of state violence during this timeframe. And there has been very little effort at restorative justice and reconciliation.

One of the remarkable legacies of these 7 decades of political turmoil and its distinct junctures is the absence of closure and serious efforts towards reconciliation or social or individual therapy. Health is as much socio-political as it is individual. It is therefore important to take stock of these decades of struggle, its successes and failures and to provide closure where possible. In this respect, the importance of Bernard Coard’s book What Really Happened can be measured.

The book is a significant contribution to Grenadian history and in particular the historiography of the Grenada Revolution. It is perhaps the most anticipated book on modern Grenadian history. At the very least, it is the only book that seeks to answer the vexing question Grenadians, Caribbean people and supporters the world over have had since the demise of the Grenada revolution: What really happened to such a hopeful project. How honestly or comprehensively Coard’s book answers this question is something that will continue to be examined. But this is not my major focus. My concern is to locate this book within the context of necessary steps towards closure, genuine truth, and reconciliation among Grenadians.

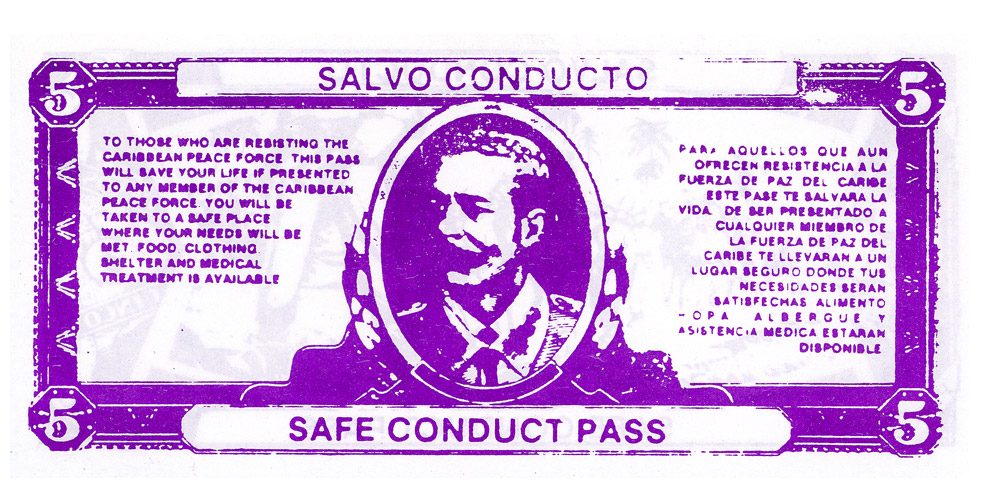

US PSYOP Aerial propaganda Leaflets to Grenada, 1983

To be fair, US invading forces in 1983 did conduct some form of mass psychological work among Grenadians. Unfortunately this psychological intervention was of the violent kind and added negatively to such a process. The US deployed an entire battalion doing this work on the population – psychological operations unit (PSYOP). According to a 1984 NYT article, these “operations command units played a key but still largely secret role in the American invasion of Grenada…” and, “…the US lost at least four men who were [specifically] killed in [these] operations.” The article concluded that much of the operations remained officially classified up to that point. It was further revealed that much of the work carried out by the PSYCOP unit was to pacify the population, and make the invaders seem as welcomed as possible. This involved painting of walls and dropping of leaflets from helicopters and presenting the revolution, and surviving party members, and the war from the US’s own perspective. Some of the works of the PSYOPs unit was exposed when spelling purporting to be locals were written in American English. So that was clearly on the side of mischief, pouring salt on psychic wounds.

The closest Grenada came since 1983 to formal, indigenous reconciliation was an attempt by the the then NNP government (1996-2000) at the turn of the century when the Grenada Truth and Reconciliation Commission began gathering information in September 2001. The Grenada Truth and Reconciliation Report claimed to be in the spirit of other national reconciliation efforts around the world. Many have attributed the Commission’s lack of success to its design and scope. Nonetheless, Grenada TRC claimed success in producing a three volume Report. An important aspect of this report are source copies of letters and statements and other documents presented to the Commission, mostly in lieu of a personal appearance in the body. It did not serve as a vehicle for the confrontation of conflicting parties working towards resolution.

In her book Between Vengeance and Forgiveness (1998), Harvard professor Martha Minow argues that reparations – whether monetary, restitution, memorials, apologies or opportunities for future education or development – serve to legitimize and acknowledge the damage suffered by victims, rather than represent any form of equitable recompense. This is why I believe that Bernard Coard’s What Really Happened? is a necessary aspect of Grenada’s reconciliation process. The book can go even further than the government initiated process to reopen this conversation, and can go a long way in helping us reach a better understanding of the tragedy. This conversation here as well as others that will sure emerge is testimony to this.

Minow, in considering the polarity between the vengeance and forgiveness dichotomies, points out that although revenge is a basic, natural, automatic reaction to transgression that can be expected and even calculated, the act of forgiving is unpredicted. Martha points out that the act of forgiving is the only reaction that acts in an unexpected way. Forgiving, in other words, is the only reaction which does not merely re-act but acts anew and unexpectedly. Yet she warns against too much forgetting, which sweeps the atrocities under the table and denies the reality of the victim’s experiences.

Alimenta Bishop and Grand daughter Nadia Bishop

Such I believe was the action of Nadia Bishop in visiting the then-still incarcerated Grenada 17 in January 1999. According to Nadia, when she forgave the man who shot and killed her father (Iman Abdullah), she began setting a more public course, hoping, she says, to enable others to realize the “state of grace” and “incredible, irrational joy” she experienced at the end of her struggle to forgive. She points out that “[her] goal was to be free of this feeling of bondage to these men, because of the hatred I felt toward them, the anger. In so many ways it feels like I had been in prison myself, emotionally, just as long as they have physically.”

Nadia posits that “[t]he end result was this really profound feeling in me that my father was very unhappy, because growing up the one thing clear was my father’s passion and love for the people of Grenada, (and) the people whom he loved so greatly, whom he considered his family, were still fighting and hating each other in his name.”

“One person I was terrified to see was Abdullah, the last person to see life in my father’s eyes, the man who actually shot him,” Bishop says. “And when I met the group, I sat across from him and didn’t recognize him. When it was his turn to speak, he said, ‘I feel even more a sense of awkwardness here, because I’m the one who took your father’s life.’ I got up, went over to him and hugged him. There could not be anything other than miraculous in that. Over the years, I dreamed of doing a lot of things to that man and it certainly was never hugging, in any of those dreams.

“I had this sense, that this was the last person to connect with my father in life. It was a sad and brutal connection, but it was a connection,” Bishop says. Ms Bishop also explained that she demanded no apologies or admissions from the men she forgave: “I didn’t need for them to acknowledge anything to me. I came. I was there for the sole purpose that I loved my father, the way my father loved Grenadians, and I felt he wanted there to be peace in his family, the people of Grenada. And it would free me to move forward in my life, and not live in the shadow of this past act.

“I think the point for me in forgiveness is freeing myself, really, of being bound to people in a negative way,” she said. “I’d encourage everyone to release conditions. You free yourself more than them.”

It is important to note too that Nadia herself was honored in her home state of California at the 12th annual International Forgiveness Day celebration in San Rafael, organized by area attorney Robert Plath (in 2008). According to her citation, she is recognize for “trying to heal her whole country [Grenada].”

In addition to these exemplary actions towards reconciliation, Nadia Bishop is but one of the many women that have had to bear the brunt of these 70 years of political turmoil that I have briefly chronicled. Some of Gairy’s most militant fighters were very poor agricultural women. Even further back, Edward Cox has indicated in the Fedon Rebellion: Causes and Consequences that many women were involved in the Fedon Rebellion. And, at the end of the rebellion, many women who were relatives of the rebels were denied reentry to Grenada after being banished to Trinidad. This should give us a sense that women played critical roles in that struggle, in spite of such examples being relegated to the footnotes of our history. The evidence of our history is there to show that women’s contribution transcend our historical timeline. Women have played extraordinary leading roles in the revolutionary process. I recall the exemplary women of my village who were the bedrock of the anti Gairy struggles, organizing the youth, hiding Jewel newspapers in their clothing and being some of the more feisty and articulate voices in the rallies. Recognizing women in the Bishop family, and especially appreciating the sacrifice of Mrs Bishop, who lost a husband and then a son in the struggle is an aspect of our reconciliation.

Bernard Coard and Maurice Bishop – Revolutionary Years

David Scott’s Omens of Adversity is another book that can provide us with some guidance as we come to terms with these legacies. Omens examines the historical trauma caused by the events of ’83, revealing why so much is at stake for historical writing about the tragedy for the Grenadian people and the wider political project of liberating the Caribbean people from neo-colonialism. And how the present is inextricably linked to the past. According to Scott, the past can be a force that strangles the present, preventing people that have gone through political catastrophe and psychic trauma from moving forward. It is perhaps ironic that the main slogan of the Grenada revolution is “Forward Ever, Backward Never.” But we must move forward and use the past, not as a burden, but as a resource that can push us forward.

Scott sees a lot of agency in the younger generation of Grenadian leaders in coming to terms with these generational trauma that paralyzed their present generation. He points to examples of the Young Leaders, a group of high schoolers whose purpose is to find the bodies of Maurice Bishop, et al. The Young Leaders see these missing bodies as symbolic of more than losing any one human death. These youngsters see the past as healable but something that can come to terms with reparative or restorative justice.

It is from this perspective that some aspects of the shortcomings of Bernard Coard’s What Really Happened can be viewed. Although Bernard Coard attributes much of the blame for the missing bodies to the US invading forces. The question is logically asked: what happened to the bodies before the US invasion, October 19-25? An understanding of the condition or location of these bodies during that time-frame may have given us a better clue about the ultimate possession of the victims of the October 19 massacre. The quest for these bodies can help bring closure to this chapter and take us closer to reconciliation thus ushering in the ‘state of grace’ that Nadia envisions. The importance of a proper burial site and funerary rites for the October 19 victim is also important in the sense that Grenada is a largely catholic-influenced country with deep traditional African retention. All-saints, for example, is an occasion in which there is informal reconciliation. Families that have been divided through conflict come together at the grave sites to pay respect to the ancestors at All-saints. It is symbolic reconciliation and memorializing. Alimenta Bishop has pointed out that even the mother of Christ received his body to be buried, declaring “how can I forgive when I don’t have [the] result about my son.”

Although it has been among the most traumatic chapters in our history, the October crisis has hastened the urgency for reconciliation. The renaming of the international airport Maurice Bishop International Airport in 2009 is another on-going act of reconciliation. And so too, it can be argued, is continuing efforts of the main political parties to actively recruit former members of the PRG from different sides of the divide into their ranks.

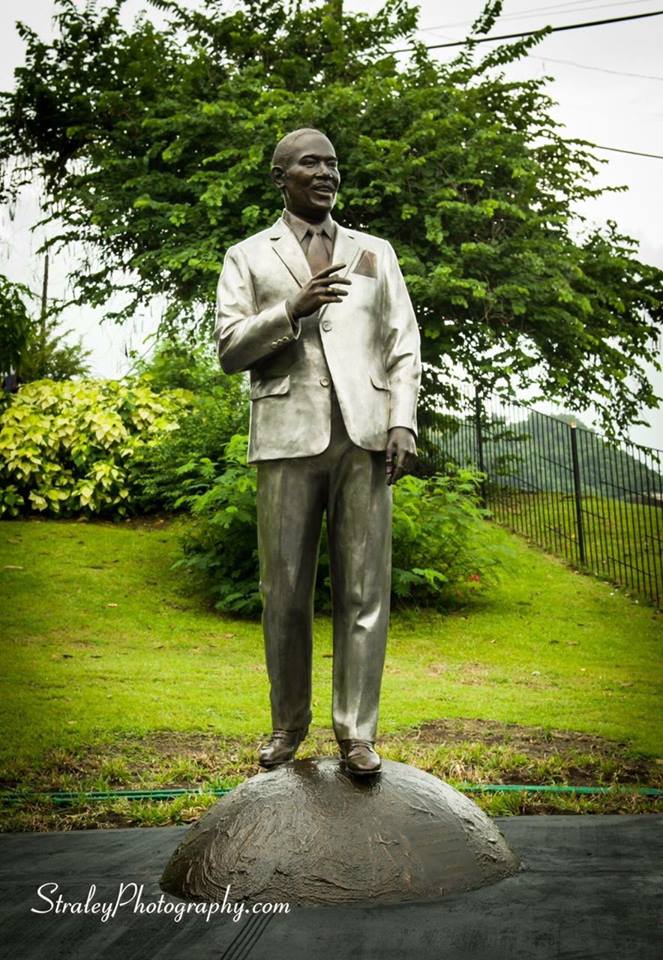

Eric Matthew Gairy

Yet another is the recent (Sept 29, 2017), installment of a full body statue of Grenada’s Father of Independence, Eric Matthew Gairy, unveiled in the botanical gardens in St Georges. The statue is among the most important monuments of reconciliation in the country today. Like him or not, Gairy is the nation’s founding father and is still respected by many, especially the older generation of working classes for the heroic struggles he led against colonialism. As an arts and literary journal, we want to recognize the work of artist Maria Mc Clafferty for her monumental work.

Reconciliation is a process and art and artists have always played central roles in societal health. How we approach these collective and individual responsibilities will determine whether, to again borrow from Langston Hughes, our past will sag like a heavy load, explode into cyclical pain, or blossom with hope and renewed vision. Big Drum Nation vows to continue functioning as a vehicle to both reflect and shape these processes.

Martin P. Felix is an editor and regular contributor to BigDrumNation.