|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 7 mins

May 10, 2024

‘No civilization of significance surrenders its riches easily… the transplanted Indian, even the most urbanized, will occasionally dream, like Walcott’s Saddhu, of the river Ganges and the sprawling fields of Bengal and Uttar Pradesh.’

The Moving Finger writes; and having writ

Moves on; nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it

(From Edward Fitzgerald, The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam)

Jhandis off Carli Bay, Carapachima, Trinidad. Photo: Courtesy Ken Jaikaransingh.

When my family moved to Port of Spain in 1953, the intention was to secure the best possible education for the children of the family. The eldest was just eight, the youngest only recently born. It was a move that, coupled with my father’s resolve to distance himself from the rice fields and difficult circumstances of his childhood in Penal Rock Road, also removed my mother from the nearby canefields of Couva and the extended family environment that she had known from birth.

For the children of the family, it meant life in an urban setting entirely divorced from the culture and traditions our parents had known. We became part of an alienated species known as the Urban Indian in a city where at the time, Indians comprised an infinitesimal part of the population, confined primarily to St James or east of Charlotte Street, and to professions as sellers of produce, newspaper vendors or City Council workers. There were lawyers and teachers, but largely mainly minority at the time.

For us, music was not of the dholak, harmonium or tassa, but steelband, calypso, and American popular music over the radio. A western tradition of British and American movies, Carnival and Christian church schools took the place of what might have been enactments of the Ramayana, pujas, Indian-made movies, Divali celebrations, and readings of the Gita or other sacred texts. Our lingua franca was English, properly spoken or not; Hindi was the domain solely of our parents at moments when they seemed to prefer to talk privately.

Therefore, it has become a voyage of discovery to rediscover the rich traditions that were lost in this transition. One becomes part of a culture only by living it; we were disconnected from that navel string to the culture that arrived in the Caribbean with the first immigrants from India in the mid-19th century, one that has impacted and shaped the evolution of Caribbean territories like Trinidad, Guyana, and Suriname in the 175 years since our ancestors first crossed the Kala pani and set foot on these unfamiliar shores. India, and things uniquely Indian, had become an area of darkness for us growing up in the city to use Naipaul’s phrase.

Journeying into that landscape is not always a process willingly or easily undertaken; for some, it never even began. One might make one’s way there via marriage and living within the culture; another might seek a way by self-immersion in the texts of the times or the writings of scholars. For myself, an occasional journey to a distant family occasion excepted, the journey began with VS Naipaul, and his introduction to a world already being altered before his eyes as early as the1930’s. Inspired by Naipaul, on then to RK Narayan’s wonderful Malgudi narratives, and Anita Desai, Rabindranath Tagore, and Khushwant Singh. Then back to the Caribbean, where an Indian presence in literature had emerged with Samuel Selvon, Ismith Khan, and Harold ‘Sonny’ Ladoo.

It is of course ironic that this flowering of Indian writing would not use the Bhojpuri, Hindi or the myriad other dialects of the first immigrants to arrive, but English, the language that paradoxically enslaved but liberated them. That tongue once mastered, initially at Canadian Mission and Maha Sabha schools, the Indian contribution thereafter to letters in the English-speaking Caribbean would expand exponentially to later include the younger Naipaul, Shiva, his nephew Neil Bissoondath and more recent names like Rabindranath Maharaj, Kevin Baldeosingh and Raymond Ramcharitar. Even more significantly, the works of acclaimed female writers of Indian origin would appear on bookshelves: Lakshmi Persaud, Shani Mootoo, Ramabhai Espinet and poet Rajandaye Ramkissoon-Chen. Each would open a window into lives and experiences hitherto unknown or unexplored.

The immigrant tongues occasionally strike back, however, words like neemakharam, jhanjat, and bhandaniya creep into the island idiom. The rules that virtually confined the early indentures to the sugar estates would enable significant traces of a mother idiom to remain, alongside other cultural artifacts preserved by those compelled to live within their own communities. Many Indians in Trinidad would begin living an ambivalent existence, neither fish nor fowl. They may have retained traditional bonds of kinship, and cultural and religious practices, for these provided a haven of sorts against the negligence or hostility of the island and its inhabitants. But a process of accommodation with the wider environment was inevitable, and a cross-fertilisation of sorts would ensue and persist.

The immigrant tongues occasionally strike back, however, words like neemakharam, jhanjat, and bhandaniya creep into the island idiom. The rules that virtually confined the early indentures to the sugar estates would enable significant traces of a mother idiom to remain, alongside other cultural artifacts preserved by those compelled to live within their own communities. Many Indians in Trinidad would begin living an ambivalent existence, neither fish nor fowl. They may have retained traditional bonds of kinship, and cultural and religious practices, for these provided a haven of sorts against the negligence or hostility of the island and its inhabitants. But a process of accommodation with the wider environment was inevitable, and a cross-fertilisation of sorts would ensue and persist.

The most significant embodiment of that engagement appears nowadays in the culinary arts, where the curries and spices brought by the immigrants have flavoured the national cuisine. Local rotis of various varieties, freely adapted from their Asian roots, have become an accepted staple of the local diet, as have talkarees and dhalls, and the ubiquitous doubles and pholourie vendors which have popped up at every street corner. Amchars, kuchelas, and chutneys adorn all grocery shelves, most made from the mangoes introduced to local agriculture by the early immigrants. The traditional Indian sweets shared at Divali or Eid celebrations – parsad, sawine, gulab jamoon, kurma, and jalebi– roll off the non-Indian tongue today as easily as they do from those of the descendants of the first arrivals.

The celebrated industry of those early immigrants, and their propensity for saving and  investment, is currently reflected today in the growth of Indian-owned enterprises nationwide. These might have been initially in dry goods and hardware stores but have spread to include investment in or ownership of large enterprises across the business spectrum. That industry would also be the catalyst for pursuing education, and the consequent profusion of Indian doctors, lawyers, and engineers (the first preferred professions), then subsequently the broader range of specialty professions made possible by the explosion of opportunities in academia, science, and technology.

investment, is currently reflected today in the growth of Indian-owned enterprises nationwide. These might have been initially in dry goods and hardware stores but have spread to include investment in or ownership of large enterprises across the business spectrum. That industry would also be the catalyst for pursuing education, and the consequent profusion of Indian doctors, lawyers, and engineers (the first preferred professions), then subsequently the broader range of specialty professions made possible by the explosion of opportunities in academia, science, and technology.

This would parallel the Indian foray into the wider culture via music, the visual arts, theatre, and sport. Works of art by individuals like James Isaiah Boodhoo and Shastri Maharaj are prominent among those now commanding international attention. The traditional melodies of India survive, but alongside a fusion of soca music in a format, perhaps disparagingly known as Chutney or Chutney Soca, embodied by performers like Sundar Popo, Drupatie, Nisha B; some like Rikki Jai even found themselves onstage in calypso tents. The Theatre Arts has nurtured talents such as Errol Sitahal, Devindra Dookie, Ralph Maraj, and the UK-based playwright Mustapha Matura.

The Hosay festivities in St James and the Ramleela observances preceding Divali celebrations are both considered  near-national celebrations. Bobby Mohammed, and Jit Samaroo became legendary names associated with developments in Steelband music, with Yohan Chuckaree the apparent inheritor of that tradition. The Indian connection with sport has been significant, especially in cricket, the latter dating back to the legendary debut of Sonny Ramadhin, a precursor to other names like Inshan Ali, Ravi Rampaul, Sunil Narine, and Nicholas Pooran. People of Indian origin now feature significantly in horse racing, powerboat racing, tennis, and hockey

near-national celebrations. Bobby Mohammed, and Jit Samaroo became legendary names associated with developments in Steelband music, with Yohan Chuckaree the apparent inheritor of that tradition. The Indian connection with sport has been significant, especially in cricket, the latter dating back to the legendary debut of Sonny Ramadhin, a precursor to other names like Inshan Ali, Ravi Rampaul, Sunil Narine, and Nicholas Pooran. People of Indian origin now feature significantly in horse racing, powerboat racing, tennis, and hockey

The process of accommodation has not always been smooth and the evolution and growth of a formidable Indian presence in politics has led to some tension and conflict with existing power groups, perturbed perhaps by the accelerated transition of once-disregarded ‘coolies’ into an increasingly vocal and significant social, economic and political bloc. Community agendas and dispute resolution mechanisms were transferred from traditional village councils and panchayats into organisations determined to secure an equitable seat at the national political table. One cannot ignore the contributions made along the way by such names as Adrian Cola Rienzi, Bhadase Maharaj, Lionel Seukeran, Basdeo Panday, and members of the Capildeo family, in what is still an ongoing process.

No civilization of significance surrenders its riches easily, nor does it always find an easy compromise with others. The original immigrant from India would have landed with seeds in both his bundle and in his psyche. Some would find fertile ground, others have withered on the branch and died. Still, even as compromises with other largely Westernised cultures are made, the transplanted Indian, even the most urbanized, will occasionally dream, like Walcott’s Saddhu, of the river Ganges and the sprawling fields of Bengal and Uttar Pradesh.

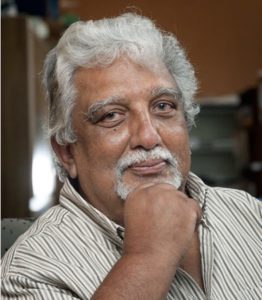

Kenneth Jaikaransingh, a former teacher, lecturer, and publisher, has authored student guides to several Caribbean Literature texts, including Plays For Today With CSEC Study Guide. His recently published collection of short stories, The Carnival is Over, is available by clicking here. He also posts essays regularly on Facebook.

Kenneth Jaikaransingh, a former teacher, lecturer, and publisher, has authored student guides to several Caribbean Literature texts, including Plays For Today With CSEC Study Guide. His recently published collection of short stories, The Carnival is Over, is available by clicking here. He also posts essays regularly on Facebook.