|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 6 mins

February 7, 2019

“The whole of nature”, wrote William Ralph Inge, “is a conjugation of the verb to eat, in the active and passive” . We eat to live and if Brillat-Savarin the eighteenth century French gastronome is to be believed, “we are what we eat”. Of course the idea that there exists a relation between food and character did not originate with Brillat-Savarin: the Old Testament anticipated him by more than 3,000 years. Now in addition to being what we eat, can it also be said that we are how we eat, the how calling attention to the rites, customs and conventions that attend our ceremonial and other eating? I believe it is so.

My Grenadian mind tells me that gastronomic talk of any kind is a mere footnote to the saracca (salacca), a ritual sharing and eating of cooked food which, typically, is “given” in a yard or an open field. The Saracca banquet is an offering to the ancestors; it is served on banana leaves laid out on the ground; the eating is usually accompanied with singing, drumming and dancing.

Saracca is an “African work” in Grenada. The word

BIG BREADFRUIT AND SARACCA NATION

This breadfruit is really a big one and in order to put our hands on it, we must go to Merle Collins’s recently released video documentary called “Saracca and Nation: African Memory and Re-creation in Grenada”. Collins, novelist, poet, historian and professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Maryland, College Park, pays homage to the Saracca Nation while deftly avoiding any explicit definition of the terms “nation” and “nationhood”. Collins’s shyness on this matter seems part professorial tease and part pedagogical prompt intended to elicit Socratic conversation. Therefore, we will take up the Collins challenge and go to battle against the two disobliging ghosts, Nation and Nationhood.

But first, what is a nation?

For our purposes I offer this definition: The nation is the community that is brought into being (and held together) in result of acts of creative collaboration undertaken by individuals on the basis of their ties of blood and /or other real or imagined bonds. Therefore, the Saracca Nation exists.

Saracca is a scarified memory and here memory is at once founding and organizing principle. Saracca is the social expression of a Yoruba proverb which says, “However far the river flows, it will never forget its source”. It is the renewal of the ancient covenants between Geenay (Africa) and faraway Babylon; between primordial tree and stolen fruit; it is the celebration of a citizenship that the body remembers and recreates in its muscled responses to the syntaxes of the drumbeat.

SARACA AND SACRIFICE

And saracca is ‘sacrifice”- my great- grandmother’s preferred word for this sacred exercise. It is a sacrifice to the gods of fertility and that is why its portions are so lavish, and why it excuses overeating-something that will attract stiff rebukes at any other time; it is also the reason why saracca dance simulates coitus.

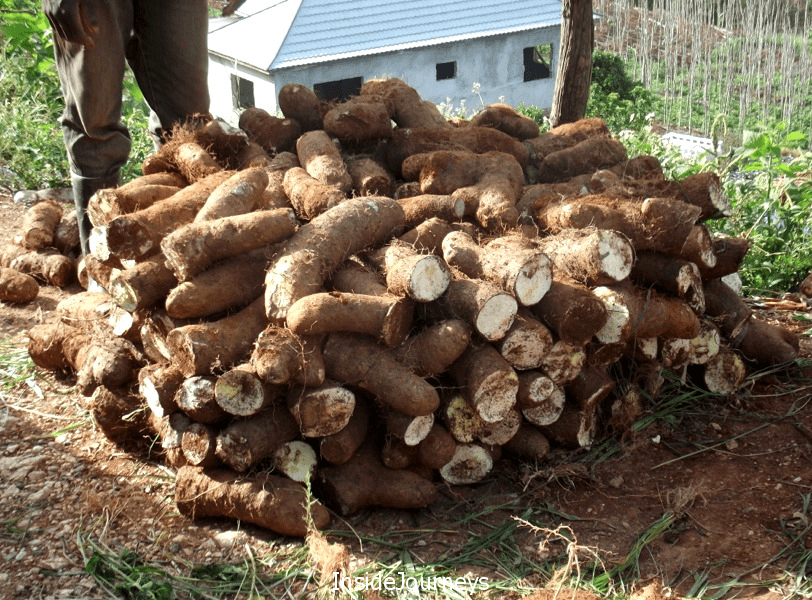

The saraca nation turns on reciprocity and food is its highest sacrament. The food-especially the items extracted from the belly of the earth-yams, sweet potatoes, manioc(cassava/yucca)-propitiate a veritable congregation of gods and ancestor spirits. Okra and corn (maize) are not hauled out of the living earth but they somehow find themselves in the upper tier of ritual significance, surpassed only by yam, the most sacred item in the foodways of the saracca world.

“I yam what I yam”

“I yam what I yam!” exclaims the unnamed protagonist in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. He had been walking along a Harlem street when he happened upon a yam seller, whose tubers kindled in him an illuminated self-knowledge. Yam runs deep within the souls of Black folk on the Continent and also in the Diasporas in the Americas and elsewhere; the Invisible Man knows this only too well.

Back on the Continent, the Igbo people hold up the yam as the “king of all crops”. It had come down to them, they say, as a very special gift of their chief god. It is the spine of their collective identity; it grows out of the divine belly of Ani, “the Igbo earth goddess who is the source of fertility and ultimate judge of morality and conduct”, according to Chinua Achebe in his classic novel Things Fall Apart (1958).

Yam is revered among the Yoruba people. Indeed, Yam porridge is the favourite food of the Yoruba god Shango, keeper of thunder and lightning. Shango’s wife Oyo chopped off her left ear and then cooked it in her husband’s yam porridge, thinking that that desperate act was going to win her Shango’s everlasting love. But it didn’t, and Oyo lost Shango to Oshun.

Yam is also stamina food among the Yoruba, who believe yam eating is the surest way to sire twins. The Yoruba have the highest twinning rate in the world so there may be some “science” in their claim. In Grenada, those who walk in Shango’s promethean light say the yam is not fit for the eating until the “thunder rolls over it and make it good”. Let’s pay proper attention here, for every use of language is an act of confession and ultimately as experimental psychologist Steven Pinker points out, “[Language] reflects the way we grasp reality”. Pinker’s view makes the case for the indispensability of the phenomenological approach to study of these matters.

Jamaica: In August 2008 Jamaica’s Usain Bolt wins the 100 metre dash at the Beijing Olympics and his father boasts that the boy’s lightning speed came from his many years of yam eating.

Yam seems implicated in the “return” to Africa of the legendary Canga Brown of Tobago. In a poem called “The Ballad of Canga Brown”, Tobago’s greatest poet, E.M. Roach (1915-1974), writes:

What gives Canga Brown that power?

He didn’t eat salt nor sugar

His flesh like Ibo yam

His blood like clean rain water

CONSTRUCTING NATION

Yam was the most important food item on the slave ship. John Barbot, the seventeenth century slave merchant, tells us that the slave ship stocked roughly 200 yams per passenger. The talk of the slave ship invokes memory of bonds that were forged in the Crossing and the fact that some Africans who sailed aboard the same ship to the Americas used the term “malungu” (shipmate) to describe each other. The word ”malungu” is derived from Kimbundu, the language of the Mbundu people of what is now Angola. Malungu ties were so powerful that there developed a strong taboo against marriages between the offspring of malungus. The idea of preserving memory seemed at the heart of the malungu ties; that same idea is the motive force of Saracca Nationhood in Grenada, Carriacou and Petite Martinique.

And there seems to be two concepts of Saracca Nationhood .There is first the nation as quilt: This is the concept of nation-hood embedded in the Carriacou Big Drum, an assembly of nine constituent “nations”- Arada, Banda, Cormantee, Chamba, Congo, Igbo, Manding, Moco, Temne.

The other view of nationhood is found on mainland Grenada and it conceives of the nation as a rich calaloo soup, a melting pot. Lena Edgar of the village of La Poterie offers a definition of “nation” which is both cryptic and enigmatic, she tells Collins:“Well, nation is nation”. What Ma Edgar is doing here is underscoring the indivisibility of nationhood. Nation is nation. It bears stating that the Carraicou view of nationhood seems demonstrably more in favour of an African continuity.

Callaoo or quilt, Collins gets high marks for giving free rein to the “Saracca people” – she lets them speak; indeed, she turns up the volume on the healing voices of elders Winston Fleary, Augustina “Ma Gus” Collins, Lena Edgar, Lizzy Thomas and Jerome Grant. In the end Collins has succeeded in giving us a beautiful gift, one which dimples the swollen cheeks of the presiding gods. The deities have signalled their delight and Collins’s kitchen will not want for anything, especially yam. And it is right that that will be so, for food is the most valuable currency in the moral and social economies of the Saracca Nation.

*Editors note: This essay is updated from the February 2011 BDN edition.

Caldwell Taylor was Grenada’s Ambassador to the United Nations from September 1980 to October 1983, and Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs from 1982 to October, 1983. Mr. Taylor is founder and editor of Big Drum Nation.

For copies of Merle Collins’s Saracca and Nation please contact Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities.