|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 6 mins

August 23, 2022

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: Hilary McD. Beckles, How Britain Underdeveloped the Caribbean: A Reparation Response to Europe’s Legacy of Plunder and Poverty: Kingston, University of the West Indies Press, 2021, 292 pages: ISBN 9789766408695 (Paperback)

The Memorial Corridor at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the USA’s first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved Black people, victims of lynching, racial segregation and Jim Crow, and police violence (Montgomery, Alabama).

The first person I heard speak of seeking reparatory justice for descendants of enslaved Africans was Randall Robinson, the founder of TransAfrica. Established in the 1970s, his organization sought to address myriad issues impacting the lives of continental Africans and their descendants in the Diaspora. He was a strident advocate of the global anti-apartheid movement and for dismantling apartheid.

Years later, his book The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks (2000) would lay out a claim for reparations to Africans Americans, both in monetary compensation and social programs to “atone for…slavery and…the imbalances, injustices, and discrimination that have left Blacks disadvantaged to whites.”

For over two decades, documentaries have been made, articles written, new organizations formed, and conferences convened from Washington to South Africa focusing on reparatory justice for the descendants of the enslaved and indigenous peoples of the world. As recently as March, Queen Elizabeth II’s progeny on their Platinum Jubilee tour of Britain’s former Caribbean colonies were reminded of that empire’s devastating legacy across the globe. It’s also important to note that in 1969 when members of the Jamaican Rastafarian community petitioned the same monarch for reparations to be repatriated to Africa during her Golden Jubilee, their demands were met with ridicule from fellow Jamaicans and the British Crown.

Many individuals of my generation emigrated from the Caribbean with little or no knowledge of the Transatlantic Slave Trade of our African ancestry.

Through incidental learning, I became aware of the U.S. government’s promise after the Civil War to award newly emancipated Black people 40 acres and a mule. That elusive remittance has entered into popular African American culture both as the name of director Spike Lee’s production company and as an expression of cynicism directed at the government’s penchant for reneging on promises to the descendants of enslaved people. In 1989, the late Congressman John James Conyers Jr borrowed the “40” for his bill H.R.40., to introduce legislation in hopes of forming a commission to study reparations for African-Americans. For 30 years, the bill was reintroduced to Congress until it finally passed in 2021, coincidentally with the death of George Floyd and the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Sir Hilary McDonald Beckles’s book, How Britain Underdeveloped the Caribbean: A Reparation Response to Europe’s Legacy of Plunder and Poverty, is a 256-page homage to Walter Rodney’s 1972 seminal text How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Vice Chancellor of the University of the West Indies, Beckles currently heads the CARICOM Reparations Commission formed in 2013, with a formal mandate to seek reparatory justice for the people of the Caribbean region. In a 1989 magazine article entitled “Hilary Beckles: Barbados’ Biggest Radical,” I interviewed the young professor who described himself as “The village boy from St. Andrew,” who drank in the rum shops and eschewed associating with Barbados’s ruling class, whom he regarded then as “culturally and socially bankrupt.” I have observed his meteoric rise through the University of West Indies system, listened to several of his lectures, and side-eyed his acceptance of the British honorific, “Sir Hilary.”

In a speech given in St. Vincent almost a decade ago, Sir Hilary Beckles noted that “…when we examine the past 100 years…and over 100 cases of reparations…weak people, disorganized people, confused people, people who have doubts about themselves, people who have no self-confidence, people who have no commitment to themselves and to their past and their children do not get reparations…” I was interested to learn of Beckles’s trajectory to guide Caribbean people toward reparatory justice.

The author begins by acknowledging Rodney as pivotal in the global reparations movement and speaks of having had “discursive sessions” with the late scholar. He shares the dedication of the text with the people and the current Prime Minister of Barbados for “raising the republic.” He makes a “clarion call” for an end to “intellectual timidity,” an interesting pronouncement given that authoritative voices like his have been mute with little or no significant analysis given to the diminishing standards of living and harsh economic reality currently facing the Caribbean masses.

The text is a brief, laying out historical evidence in the court of public opinion on why the accused – Britain – must pay its former Caribbean colonies reparations. The writer outlines that emancipation and independence from the British was a political exercise rather than a financial one. Beckles emphasizes that after the 1930s revolts and later calls for independence, Britain deliberately set out to “suppress regional economic development…and thereby solidified relationships and institutions that kept the region poor and dependent.“ Nonetheless, men like Eric Eustace Williams and Sir Alexander William Bustamante understood that poverty and underdevelopment would come with the end of colonial rule if Britain were unwilling to offer reparatory funding. Having extracted the Caribbean’s wealth for centuries, the former colonies were supposed to become miraculously self-sufficient in the postcolonial era.

Beckles has set out a three-prong approach: outlining the origins of slavery in the Caribbean, making his way through the fifteenth century (“Columbus Economy”) to the present state of the English-speaking Caribbean, where exists “the highest poverty in the newly independent world.” He discusses the origins of the mercantile system; gives an overview of the genocide of natives, the enslavement of Africans, and the extraction of wealth by European powers. He establishes his premise that the Caribbean is unique in that the Western economic system was created for the primary purpose of exploiting the resources of these colonized nations for the “exclusive economic benefit” of the West. The Caribbean poor, relegated to the “slums of empire,” is evidence of the “colonial mess left behind by Britain.”

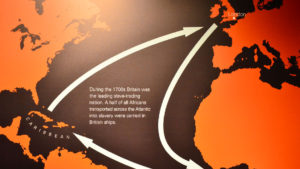

Diagram of the Transatlantic Slave trade: During the 18th century Britain was the leading slave-trading nation. Half of all Africans transported across the Atlantic into slavery were carried in British ships.

The text indicts the banks and insurance companies of the Western European capitals who enslaved over 10 million Africans into the Caribbean system of enslavement, with most being sold by Britain. The author discusses American investors and their involvement in Cuba and other Caribbean economies after the Civil War of 1865. He documents the series of U.S. invasions and occupations of Caribbean territories and the formation of corporate plantations. He posits that Britain’s accomplices, “the Americans…remain the principal producers of Caribbean poverty.” He makes exhaustive comparisons between the East Indies and the West Indies to highlight how one sphere of the British empire fared over the other. Beckles writes that in private, Britain has admitted to the debt it owes the Caribbean but publicly denies it.

The book contains evidence proving that Britain sought to “keep capital away from the region to further its underdevelopment” after emancipation. Beckles stealthily addresses and sidesteps the British defense that decades of incompetent Caribbean leadership and corruption are to be blamed for the region’s underdevelopment. However, in laying the blame totally on the former colonizers, one wonders whether Beckles tacitly gives cover to Caribbean post-independence elites.

I found Beckles’ explanation of the demise of a federated West Indies, initially proposed by Marcus Garvey, enlightening. He uses the metaphor of the British’s disingenuous celebration of the birth of the Federation, then starving the infant by denying it the necessary funding. It has passed into a legend that the failure of the Federation belonged to egotistical Caribbean leaders who couldn’t decide on a leader rather than the stratagems implemented by the British to “discredit” and “discard” the union.

This text is undoubtedly well researched, as exhibited in the 35 pages of bibliography and index, voluminous footnotes, and archival documents substantiating Beckles’s stamina for delving into the historical weeds. He has procured the statements of myriad leaders, including Sir Winston Churchill, correspondence from subalternates of the empire, and politicians. He has included quotes from former UK Labor PM David Cameron to bolster his case that British governments have fostered policies of resentment and punishment toward the region and have been cavalier in their response to its persistent poverty and underdevelopment. The historian has also documented the gallant efforts of Caribbean leaders and activists and the immoral financial and psychological weight they and their people have had to shoulder.

Having waded through statistics and document excerpts, I was anxious to get to the case section that lays out how the defendants will be made whole – what Beckles alludes to in his introduction as “new rules” – to settle the debt owed to the Caribbean. The book ends. Then in an Epilogue, Beckles calls for the British to return to the scene of the crime. He wants a “reparation-for-development summit” to set a mutually agreed partnership for prosperity. Something similar to last year’s conference coined Durban II, where the UK and U.S. were conspicuously absent.

This text will be added to the canon of literature on reparations for descendants of enslaved Africans. It will affirm Beckles’s earlier ambition to “master the craft of historical writing.” One wonders, though, how the book will improve the current conditions of alienated youths in the Caribbean. What is being done by the ministries of education and the region’s universities to build the self-confidence and self-respect that the writer contends is needed for future generations? How does the reparations movement transcend from exhaustive research to mass advocacy?

Margaret Prescod-Cisse, a former English Teacher in Barbados and the USA, is a frequent contributor to Medium, a web-based writers forum.

Margaret Prescod-Cisse, a former English Teacher in Barbados and the USA, is a frequent contributor to Medium, a web-based writers forum.