|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 7 mins

August 23, 2022

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: Hilary McD. Beckles, How Britain Underdeveloped the Caribbean: A Reparation Response to Europe’s Legacy of Plunder and Poverty: Kingston, University of the West Indies Press, 2021, 292 pages: ISBN 9789766408695 (Paperback)

“Dr. Beckles has written a book rich with emancipatory promise… [a] worthy addition to the compendium of development studies, and West Indian economic and political history, [which] must be read by all those seeking an engaged understanding of the historical circumstances that have profoundly influenced our contemporary Caribbean.”

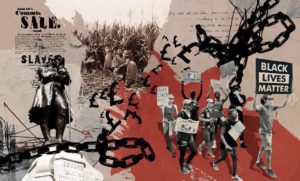

The contemporary Caribbean presents an interesting duality. Once the site of intense contestation amongst competing European powers, the Antillean world of today occupies a rung on the outer reaches of the global economy. Whereas formerly, its slave-based plantation economy had produced sufficient wealth to fill mercantilist Europe’s coffers, by the mid-19th century, its economic fortunes had been eclipsed by the emerging industrial juggernaut of the North Atlantic region.

Dr. Beckles shows that so pronounced was this transformation and so jarring its effects on both the British Imperium and their local agents- the plantocracy- that strenuous efforts were made to maintain the local power balance by keeping the newly “emancipated” toilers in as close to a state of penury and servitude as was possible.

This fracturing of hope for an equitable and well-balanced society is amply revealed in Dr. Beckles’s timely and well-researched book, “How Britain Underdeveloped the Caribbean…”. Here he presents us with a profound historical analysis of today’s Caribbean laboring under the stygian shadows of a past which continues to exert multi-dimensional and generally negative influences on our lives.

To this end, he employs and extends the development/underdevelopment paradigm and explains the Caribbean’s decline from economic centrality to one of irrelevance in the global economy. At the heart of this schema exists a symbiotic relationship between two regions of different strengths, involving a tight embrace whereby the economic lifeblood of one is gradually squeezed out by the other.

A central feature of Dr. Beckles’ exposition is that it demonstrates Britain’s nefarious role in this exploitative relationship. First, through its extraction of the economic surplus from the West Indies and later, through repeated attempts to block its economic progress in the post-emancipation period. Beckles notes, “[the British Government] fossilized the racialized economic and social structure in tandem with a repressive political framework intended to maintain the economic dependency of the region.” The acquisition of this unreimbursed wealth, it must be noted, seeded in no small measure the technological transformation that would eventually mature into the Industrial Revolution.

Yet today, the Caribbean, having been bled so that the Euro-Atlantic world may thrive, occupies an uneasy position in the global economic hierarchy. With its aspirations of a North Atlantic standard of living blunted by heavily distorted and fragile economies, a comprehensive historical investigation of how this “underdeveloped” status arose assumes utmost importance.

Yet today, the Caribbean, having been bled so that the Euro-Atlantic world may thrive, occupies an uneasy position in the global economic hierarchy. With its aspirations of a North Atlantic standard of living blunted by heavily distorted and fragile economies, a comprehensive historical investigation of how this “underdeveloped” status arose assumes utmost importance. One is, thus, unsurprised when Dr. Beckles reveals that it was never the aim of British imperial policy to oversee the development of a balanced Caribbean economy geared as much to internal consumption as it was to the external market. Indeed, the long, unforgiving centuries of slave labor, ceaseless and brutal in all its physical and psychological aspects, gave adequate warning that Christian charity was severely outmatched both by the system of white supremacy and by the profit motive. Moreover, as Beckles notes, in the post-emancipation era, Britain, aware of its position as the avatar of Christian civilization, was not willing to be accused of indulging the newly freed Afro-Caribbeans in their supposedly wanton and indolent ways.

This attitude was fortified by the tenets of British racial philosophy, which held that black people would drift aimlessly into a degenerative state without the firm hand of white authority. Towards this end, the British employed a dual-track policy: First, support for the local plantocracy meant that the overriding purpose of economic life in the Caribbean was to cultivate export-oriented crops on every suitable acre. The newly emancipated toilers were forbidden from owning even a small acreage where they might have sought to keep body and soul together. Inevitably, the threat of famine not only lurked but pounced.

From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, famine ravaged the region from Jamaica in the west to the eastern Antilles. What could have been avoided by shifting part of the arable acreage towards local consumption was, in the grand tradition of Europe’s civilizing mission, not to be. Black lives were indeed expendable. In 1897, the dire economic conditions that this outlook engendered sent the British off on one of their periodic governmental forays. The result, not unexpectedly, was the proposal of pseudo-solutions to the daunting problems plaguing West Indian development.

From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, famine ravaged the region from Jamaica in the west to the eastern Antilles. What could have been avoided by shifting part of the arable acreage towards local consumption was, in the grand tradition of Europe’s civilizing mission, not to be. Black lives were indeed expendable. In 1897, the dire economic conditions that this outlook engendered sent the British off on one of their periodic governmental forays. The result, not unexpectedly, was the proposal of pseudo-solutions to the daunting problems plaguing West Indian development.As Dr. Beckles has shown, the Colonial Office dispatched a Royal Commission of Inquiry to the Caribbean. Unfortunately, like all the others that followed–the 1929 Colonial Development Act; the Moyne Commission of 1938; the West India Royal Commission (1945 )–the Royal Commission of 1897 contained deluded schemes for economic revitalization. It was built on the twin strata of black moral degeneration and the imperative that the Caribbean economy should remain a distorted, agriculture-focused entity, shorn of all but the most elementary forms of industrialization.

The second track was, of course, the military option. As Dr. Beckles has shown, the British were not reticent in employing their police and military powers. The history of this post-emancipation period bears witness to the many Afro Caribbean lives lost to the pacifying impulses of the Imperium. Dr. Beckles underscores this disturbing feature, noting that from the 1860s onward, “across the West Indies, Guiana and then Jamaica became the epicenters of mass killings.” In Morant Bay alone, several hundred Afro-Caribbeans were slaughtered on orders of the British in 1865. This militarized response to any sign of demands for human rights and dignity continued into the period of labor unrest of the 1930s.

If the military option was an indispensable response to any perceived disturbance in the social order, then the ideological war waged for centuries against black people did its nefarious work insidiously. The constant articulation of black inferiority by racial ideologies of the British Empire and the explicit racial cast embedded in colonial policy meant that the Afro-Caribbeans were constantly physically and psychologically threatened. Yet, despite such unrelenting onslaughts, the Afro-Caribbean spirit was not broken. Dr. Beckles brings to light those who heroically resisted the horrors of Afro-Caribbean life due to British imperial policy. Against this backdrop of malign neglect, Dr. Beckles raises the issue of reparations.

While this is a necessary step towards some form of regional economic resolution, a certain disquiet persists. How can we move the Imperium–which, at the height of its power, fought relentlessly against dispensing any meaningful economic assistance to the Caribbean–to ethical and life-sustaining action, which is the moral core of reparatory justice? Britain’s involvement with the question of reparations carries more than a bit of hypocrisy.

In the aftermath of the First World War, England sought massive payments from defeated Germany. Yet, Prime Minister Lloyd George was vehement in his opposition to any form of reparatory justice for the formerly enslaved Africans and their offspring. Given Britain’s long-standing intransigence, a grassroots movement will have to exert moral and political pressure on the now diminished hegemon, a self-imposed castaway shorn of its continental support and still unwilling to acknowledge its crimes against the African people.

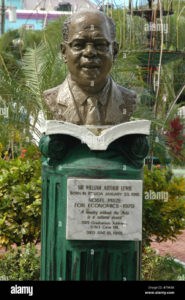

Perhaps, Dr. Beckles places too much faith in the ameliorative powers of reparations and the belief that they could serve as the basis for developing a self-sustaining/autonomous economic formation. He discussed the highly debilitating Caribbean debt, “which nullifies the potential for growth.” The author observed, “The call here is for a discursive return to the reparatory justice approach to economic development that provides an opportunity to transition from the aid-debt entrapment to an investment orientation.” Further on, he summarizes the renowned Caribbean economist Sir Arthur Lewis’s position, “There had never been any credible reason to assume that the British government would adopt a development policy that called for an injection of significant capital into a post-slavery colony.” This thus raises the question: Is “a reparations approach to social justice,” as outlined by Lewis in 1954, possible today?

Perhaps, Dr. Beckles places too much faith in the ameliorative powers of reparations and the belief that they could serve as the basis for developing a self-sustaining/autonomous economic formation. He discussed the highly debilitating Caribbean debt, “which nullifies the potential for growth.” The author observed, “The call here is for a discursive return to the reparatory justice approach to economic development that provides an opportunity to transition from the aid-debt entrapment to an investment orientation.” Further on, he summarizes the renowned Caribbean economist Sir Arthur Lewis’s position, “There had never been any credible reason to assume that the British government would adopt a development policy that called for an injection of significant capital into a post-slavery colony.” This thus raises the question: Is “a reparations approach to social justice,” as outlined by Lewis in 1954, possible today? Indeed, the question of reparations is a troubling one. There have been attempts at restoring some forms of reparatory justice. However, these have generally been geared towards a particular audience, e.g., a university granting scholarships to descendants of people it had formerly enslaved. As such, these reparations are localized and, inevitably, narrow in scope.

Dr. Beckles’s concept of reparations is far more expansive–including seeking reparations for Caribbean Indians who were subjected to deceptive indentured service–than the compensatory efforts undertaken by private institutions. It could not be otherwise, for Dr. Beckles is concerned with nothing less than the invigoration of national economies operating well below their capabilities, which can be directly tied to the aforementioned centuries-long pillaging.

Today, the Global South faces a future riddled with fading possibilities. The roiling economic debates of decades past have long since retreated from the stage: the import-substitution model of the Economic Commission on Latin America (ECLA), the South-centric approach of the New International Economic Order (NIEO), the heavily statist nature of the non-market dominated economies of the East, all have fallen before the almost irresistible force of neoliberalism. In the Caribbean, as elsewhere, the question of what is to be done has seldom been more in need of an effective answer.

Dr. Beckles has written a book rich with emancipatory promise. “How Britain Underdeveloped the Caribbean: A Reparation Response to Europe’s Legacy of Plunder and Poverty” stands in the grand tradition of George Beckford’s “Persistent Poverty,” Eric Williams “Capitalism and Slavery,” and “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa” by Walter Rodney. These works apply a critical gaze to the traditional, British–infused historiography, centering their analysis not on the supposed defects of the Caribbean people but on the structural impediments imposed by the now faded empire. This worthy addition to the compendium of development studies, and West Indian economic and political history, must be read by all those seeking an engaged understanding of the historical circumstances that have profoundly influenced our contemporary Caribbean and areas of the Global South facing similar circumstances.

Lester Adams is an independent researcher based in New York.