|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 5 mins

February 26, 2023

Last year, in the lead-up to the 60th Anniversary of TT’s Independence, many media discussions and promotions focused on the significance and achievements of the occasion and history and assessing the Independence and nation-building experience. Inevitably, the 1970 Revolution came up. Different views assessing significant development varied from describing it as a dark period to a negative in the Independence journey. Some even equated it with the July 27, 1990, attempted coup.

One host, however, said that 1970 must be seen as a positive experience for our young independent country because it brought about several positive changes, significantly the creation of employment opportunities denied many young, educated people who had been excluded from the banks and other institutions because of persisting racial discrimination.

This piece attempts to put 1970 in perspective; what led up to it just eight years after the heady atmosphere of anticipation as Independence approached, the nature and significance of 1970, and its influence on the nation-building project. There are now several articles, books like POWER – Interviews 1970 T&T Part 1, edited by Chike Pilgrim, and video presentations like ’70 Remembering a Revolution describing the atmosphere and events of 1970, including analyses published on the occasions of the 20th and 50th anniversaries of the ’70 Revolution.

Several cultural shows and performances, like Rawle Gibbons De Roaring 70s, various calypsos, and other expressions of the visual and performing arts, also record that critical period, including exhibitions by the National Trust at Nelson Island and records of the National Archives.

The Turbulent 60’s

The country’s economy had become heavily dependent on the oil industry heading into the 1960s. “The oil industry … became the main factor in the country’s GDP and exports (up to 80% of foreign exchange earnings by 1960-61). Economic growth of 8-10% per annum in the six years leading to 1961 declined to 1% in 1962 as world oil prices plunged”[1]. So, at the advent of Independence, the economy experienced difficulties as oil prices slumped in 1962 and other sectors were not creating jobs or foreign exchange earnings as projected.

The country’s economy had become heavily dependent on the oil industry heading into the 1960s. “The oil industry … became the main factor in the country’s GDP and exports (up to 80% of foreign exchange earnings by 1960-61). Economic growth of 8-10% per annum in the six years leading to 1961 declined to 1% in 1962 as world oil prices plunged”[1]. So, at the advent of Independence, the economy experienced difficulties as oil prices slumped in 1962 and other sectors were not creating jobs or foreign exchange earnings as projected.

“The workers and their unions were fighting battles to save jobs as employment in oil fell by 3% between 1965 and 1969. Automation in sugar led to retrenchment, and in other sectors, job cuts were the order of the day. In June 1968, 10,000 workers joined in a March of Resistance. The Public Transport Union (TIWU) led the challenge against the Industrial Stabilization Act (ISA) with strikes at Sissons Paints in 1967 and in public transport in June 1968 and the May 1969 Bus strike.

The disaffected among the unemployed and the intelligentsia at UWI were also in action. Some lecturers were challenging the thinking and policies of the Government. The university students protested on 26 February 1970 in support of 11 Trinidadian students arrested at Sir George Williams University in Canada”[2].

“On March 18, 1965, the Government released the report of the Mbanefo Commission, which was set up in 1963 to investigate what the government and some ‘conservative’ trade unionists called ‘subversive political activity’ in the trade union movement. In just 48 hours, 18-20 March 1965, the Industrial Stabilisation Act was passed in Parliament and assented to by the Governor General. This law was principally aimed at restricting the workers’ right to strike. It banned strikes in ‘essential services’ – electricity, fire, health, water, and sanitation. It introduced compulsory arbitration at the Ministry of Labour and the Industrial Court.

Williams himself later declared that the ISA was aimed against “the subversive elements in the society.” and that the “background was an open attempt to link the trade unions in oil and sugar”[3] (Eric Williams, Inward Hunger, p 311)

“All these currents fed into what erupted on 26 February as the 1970 Revolution led by the National Joint Action Committee (NJAC), formed by students, youth, workers, and their unions.

In 1970, mainly young persons, disillusioned with the persistence of the colonial construct, sought to address social inequality, foreign domination of the economy, racial inequality, and poor political representation”[4].

Other authors have analyzed the 1970 Revolution, pointed to the same factors contributing to the explosion of dissatisfaction and discontent, and compared the ’70 Revolution to the 1937 Butler Riots[5].

The Revo and the Response

The 1970 Revolution was the second attempt by segments of the population to intervene and give definition to the nation-building project. The first was the work of Pegasus and its creation and preparation of its Project Independence plan for nation-building between 1962 and 1967. Not accidentally, the same man was to play a leading role in founding the organizations that led both attempts as people’s definition of the nation-building project – Pegasus and NJAC.

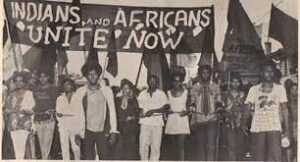

The shouts of “Power to the People” and the sound of marching feet filled the air. The clarion call “Indians and Africans, Unite!” urging unity of the People was inscribed on the banner. The youth re- examined history, seeking a better understanding and appreciation of the society and its people and defining project independence anew.

examined history, seeking a better understanding and appreciation of the society and its people and defining project independence anew.

The response of the ‘independence’ state was a mixture of ignoring ideas for a new development approach, offering a minimum of concessions, a State of Emergency, imprisonment of leaders, and brutal repression, including the attempted dreaded Public Order Bill, which was aimed at curtailing Rights to Protest. Like the colonial authorities’ response to the Butler Riots, the approach to the 1970 Revo was ‘Smiles and Blood’ – token concessions and severe repression. Against those who dared resort to arms, the answer was blood and steel. Against the adherence of the youth to revolutionary ideas of change, a new element was introduced to society – the mass culture of illicit drugs. A series of “Woodstock” events became an outlet for promoting narcotic drug use”[6].

Some of the deepening problems of violent criminality and social decay that we face today, like the record murder toll of more than 610 in 2022, can be traced back to the very responses of the state and the controllers of economic and political power to the people’s intervention in the 1970 Revolution. 1970, therefore, is not a dark day for our Independence. It was part of the birth pangs of our newly independent country and society seeking to chart its way on the path of nation-building as sovereign people taking charge of their own destiny.

Project Independence: After 56 Years is available here.

[1] Weatherhead, Clyde, Project Independence: After 56Years, 2019, pp 24,26

[2] Ibid, pp 44 -45

[3] Ibid, pp 42-43

[4] Ibid, p 45

[5] Taylor, Fiona-Ann, Two Twentieth Century Upheavals in Trinidad: the 1937 Labour Riots and the 1970 Black Power Uprising, a Comparative Analysis. Diss. The University of the West Indies, 2002.

[6] Weatherhead, Clyde, Project Independence: After 56 Years, 2019, pp 46-47

Clyd e Weatherhead is a Citizen and Advocate for Democratic Renewal of our Society and Governance.

e Weatherhead is a Citizen and Advocate for Democratic Renewal of our Society and Governance.

According to Valentino, like all that history means nothing. We do have to be careful not to toss the past unwittingly into the future. But the future, as we can see, can become a mere projection of the past, bearing close resemblance to the days of dogma and unbridled counter revolutionary unconsciousness. And yes I still smile when I am greeted in the bank by Afro and indo Trinis. If they only knew…

I was not aware that what we were working on would be packaged with a Clyde Weatherhead’s piece, whom I know personally as we were colleagues (basically I mentored under him and other older teenage activists in the earlies) in organizations at the onset of both of our activist lives. His piece is not bad, but is critically flawed (if not fatally) with respect to equating 1970 with Geddes Granger’s Pegasus project, as a kind of 2nd attempt. Pegasus was a contending view to not only the PNM/Williams/DLP approach to nation building, but also to other clearly more progressive visions being advanced by CLR and what became his Workers & Farmers Party, as well as by other leading personalities including George Weeks, Joe Young, James Millette, Winston Suite, Clive Nunez and others. In that sense, Pegasus was NOT the forerunner to 1970. Nor was it ever a mass movement, which clearly sets 1970 apart.

Yes, all of the above belong to the broad conversation about which path and direction the nation should persue. But as much deep ideological divides existed between Ganger’s vision and that of the more progressive forces addressing that challenge. Finally, the problem of out of control crime, the frustration of the younger generation belong alongside the failures and reversals (economic, cultural etc) as consequences stemming at least in part from the suppression of 1970 and of the opportunity and vision it represented, should not be equated with consequences of Pegasus vision not prevailing. That’s quite a stretch. Pegasus was a very different animal to 1970. In fact, before the close of the 1970 year itself, those deep divides were already being reflected in substantial sections (my contention) of the socially conscious and activist youth moving beyond NJAC and Makandal, as I vividly recall. Indeed, Weatherhead himself was part of that very phenomenon in the earlies.