|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Reading Time 8 mins

April 4, 2023

“I later realized that [Dr. Williams’s] political interest was not in relieving the victims of capitalism and slavery but in quelling all threats to his authority and the State.”

As an officer in training at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst (RMAS), in Camberley, England, from 1965 to 1967, I wrote love songs to Lorna and poetry to Claudette in the middle of the harshest winter during mock battles on the Salisbury plains. The rapid bursts of machine gun fire were music to my poetic mind.

A guava flower out of season

a poet trained at Sandhurst

I seek shelter from your ceremony

of sword and salute

to drift not far from myself.

I was a perfect oxymoron of a soldier/poet – dedicated to eliminating particular human beings, if necessary, and generating life-transforming metaphors. Already, I was poised to dance between the competing demands of social imperatives. I was unaware of Gandhi’s influence then, but “You must become the change you want to see” rang incessantly in my ear.

I captained the RMAS soccer team, opened the bowling for the Normandy Company cricket team, and boxed for the Academy as a light heavyweight against other military units. A busy sporting season boosted my academic performance, and I excelled at Military History, English Literature, and Chemistry.

I experienced a surge of unconditional personal power. I loved it. I wanted more of it. A great deal more. I had the feeling that I could accomplish anything. Training along the obstacle course, precision drilling, or shooting on the rifle range – all were joyful adventures. Little did I know I was infuriating some of my fellow cadets with my high personal performance.

My body somehow accustomed itself to the fluid days of the Academy. Those were days when the sun spread a soft smile from London to Camberley, and the Academy returned greetings with heavy boots in harmonious if loud, orchestration. With his rhythmic bark, Sergeant Hall ordered our heels to dig into the parade square. Chest up! Neck on the back of the collars! Heels! Heels! Heels!

At the graduation ceremony, Field Marshal Montgomery presented me with the “Best Stick” for having topped the ranks of overseas cadets. I felt pride and took his whispered advice that “People always matter.” Of the many lessons I learned at Sandhurst, that one stuck with me. People matter.

I was mindful that Sandhurst was intended to be the breeding ground for young British military elites to be insulated from external political influences and social upheavals. But with the pervasiveness of worldwide social unrest and in the era of television and the medium of mass communication, images of protest, war, repression, and racism came alive nightly on the news and other programs. Isolation from the real world was not possible. The show went on, nevertheless.

I was amazed at how the reluctant tarmac absorbed details of difficult days in Trou Macaque, my, in Sparrow’s terms, ghetto village “with fire and brimstone up in Laventille,” illuminated by the calypso’s telling essential truths through distortions. With each dig of the heel, my boyhood flung past khaki trousers embellished with pleats so well defined they ushered in an era of new manhood, a redefinition of my life, forever. Sharp as a tact was no longer a metaphor but what I became.

When I returned to Trinidad in 1967, highly accomplished, I noticed that my confidence infuriated many senior officers. In any event, I felt certain that I would rise to the top of the Trinidad and Tobago Regiment (TTR) and enjoy a career not prophesied by my mendicant days as a ghetto kid from Trou Macaque, Laventille. I committed to being the best Regimental leader ever.

I had so thoroughly absorbed the powerful impact of my Sandhurst training, my conversion from boy to man, from civilian to soldier, I felt superbly confident I could contribute to social progress via a military career. Sandhurst was the acme of professional training. Even my nascent spirituality found nourishment in Father Moxley’s public admiration of the Christian mystics in sermons he preached on Sunday mornings as the head priest in the Academy’s Roman Catholic church.

None of the “short service” senior officers welcomed me back from Sandhurst or spoke openly of my accomplishment. I felt out of place among a clique of boastful, arrogant officers whose commission into the officer ranks followed the usual cull of family privilege and political favors. I know now that their incompetence comforted the political directorate because their ineffectualness posed no threat to them. Nor were they enlightened to the new thinking of Black liberation.

“[M]embers of the rank and file… were running from their own Trou Macaque. In a way, TTR was their redemption from poverty, as it was mine.”

But members of the rank and file read the story in my eyes. They, too, were running from their own Trou Macaque. In a way, TTR was their redemption from poverty, as it was mine. TTR was one way to position ourselves for a likely intervention into the economic disparity of Afro and Indo-Trinidadians, but we were not hardened military personnel; instead, we were poets and comedians, calypsonians and journalists, fathers and lovers who found a place where, in mutual protection, we could pretend long enough till the next leg of the journey.

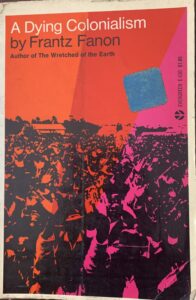

During this period of military service, many questions occurred to me regarding the plight of the dispossessed and the apparent inability or unwillingness. of the economically advantaged to treat the despair of the poor. This attitude was mirrored within the military as ordinary soldiers were treated with scant regard for their contribution. These reflections initiated my adventure into understanding revolutionary action in the writings of Franz Fanon and the poetry of the Martiniquan poet Aime Cesaire.

Would you believe it? Fewer than three years later, I heard the heavy metal door of a Royal Gaol cell close behind me, and within a week, in frustration and deep disappointment, I was pounding the cold concrete walls of a prison cell on Carrera Island. I had dared to express my support for the young Sandhurst-trained mutineers and the Black Power movement.

1970 was a year of dramatic anti-government protests in Trinidad and Tobago. Beginning in the late sixties, ghetto voices were rising in objection to the government’s inability to curb the plight of the poorest. The vice of desperation tightened around the poorest of us everywhere, and everyone was desperate. Some were lucky enough to escape the vice by joining the military or the police force. Certainly, Sandhurst was my redemption from gang warfare, incessant deprivation, and little to quell the grumbling in my empty stomach. Notwithstanding the pervading social conditions, Dr. Eric Williams, the Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago then, had told my father that his government had to set an example to discourage others from daring to challenge his authority and the State. I later realized that his political interest was not in relieving the victims of capitalism and slavery but in quelling all threats to his authority and the State.

The young Sandhurst officers (Raffique Shah, Rex Lassalle, Michael Bazie, and others) met weekly to reflect on the state of the military and ponder our role in the social chaos. One week before the assassination of Martin Luther King, we were searching our consciences to determine whether we would bring our military training to defend the tyranny of the minority and the injustice of the times in Trinidad and Tobago.

Following Che Guevara’s murder in Bolivia in 1967, 1968 was already tumultuous with international wildfires of leftist pushback. From continents to island nations, the growing discontent simmered. Discord was ubiquitous. Economic disparity, racial injustice, and deep poverty scarred the landscape.

It was a time of profound unrest. Conflict was everywhere. This was no mere Calypsonian the Mighty Duke exhortation for us to be proud of the color of our skin. We  realized for the first time that the chief instrument of any cultural change could not exclude our talent for speaking with revolutionary fervor. After all, we had all read Che Guevara, Franz Fanon, Aime Cesaire, and other revolutionary writers and thinkers of the day. We followed Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X as they fought to inject regulating ideals and new meaning into civil disobedience as an effective protest tool.

realized for the first time that the chief instrument of any cultural change could not exclude our talent for speaking with revolutionary fervor. After all, we had all read Che Guevara, Franz Fanon, Aime Cesaire, and other revolutionary writers and thinkers of the day. We followed Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X as they fought to inject regulating ideals and new meaning into civil disobedience as an effective protest tool.

But with incredible haste, a conspiracy flourished among the military brass and the political hierarchy, and one of the pride of Sandhurst became a prisoner of the State. The presiding judge of the court martial banged his gavel on the improvised desk and pronounced: “For conduct unbecoming an officer, I hereby sentence you to two years imprisonment!”

My heart sank. My mind went numb, and my entire body became limp. But I pulled it together quickly, Sandhurst style, and walked with forced residual pride the short distance to the Regimental vehicle that would transport me to the Royal Gaol at Frederick Street, Port of Spain.

In retrospect, many contingencies have befallen me in my lifetime thus far, but this declaration of my imprisonment was devastating. It was an excruciatingly rough conclusion though a serious start to something new.

Many years later, Neil deGrasse Tyson, the famous American astrophysicist, gave me a more empowering perspective. He argued that, following Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, human beings are the evolved product of stardust from a cosmic sneeze that formed the planets that gave rise to various forms of life, including all life on Earth. This challenge to my Sandhurst understanding of the creation story fell neatly into my perennial doubt about the social conditions we get born into.

Indeed, as my father would later confess, my view was locked onto the stars decades before Dr. Tyson revealed that we are all products of stardust. The cosmos was the call. My Sandhurst colleague, ex-Lieutenant Michael Bazie, reminds me of a note I wrote to him from London in 1967 in which I asserted that we were just insignificant particles in the storm of evolution. I can now add that we are mere specks of stardust in this vast cosmos.

It was more than likely this unconscious insight into a cosmic perspective that conveyed the incredible calm that saw me through those early days of severe disorientation and the unexpected, rugged preparation for another kind of possibility.

Indeed, Michael Bazie, on reading this opening chapter, commented:

January 23, 2023

Dave,

Not unusually, I read your response with enjoyment. Not a day passes without some circumstance causing painful awareness of the persistent sequelae of “miseducation.” Your own reference brought a momentary and pleasant pause to the reading. Somewhere in my youth or childhood, I recalled the poem by D H Lawrence, “Snake,” in which he stated: “I despised myself and the voices of my accursed human education.” This concept of “Awareness” causes me to be happier with the “Me” that I am today. Admittedly, the journey is inspiring but, nonetheless, endless.

* Excerpts of David Brizan’s forthcoming book: From Sandhurst to Star Dust. © 2023 by David Brizan

Dr. David Brizan, a graduate of the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, is a Leadership and Life Empowerment Coach working at the intersection of creativity and pragmatic action. He is the inventor of the VICAR model of constructive living and C2nd Linguistic Strategies. His work delivers unconditional personal power (UPP) with models, tools, and empowerment techniques through Responsible and Rugged Individualism (2RI). He is a regular contributor to BigDumNation, and his writings have also appeared in Everybody’s Caribbean-American magazine.

Dr. David Brizan, a graduate of the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, is a Leadership and Life Empowerment Coach working at the intersection of creativity and pragmatic action. He is the inventor of the VICAR model of constructive living and C2nd Linguistic Strategies. His work delivers unconditional personal power (UPP) with models, tools, and empowerment techniques through Responsible and Rugged Individualism (2RI). He is a regular contributor to BigDumNation, and his writings have also appeared in Everybody’s Caribbean-American magazine.

Thoroughly enjoyed the read!

Excellent start to what will be a seminal piece of work, made more stellar because it is so true. Waiting for the rest

Inspiring.

I would like to chat with you about Sandhurst and 1970.